Making (great) decisions, part 2

In part 1, I looked at simple methods of delegating or prioritizing decisions, and one option for making decisions quickly based on “operating principles.”

This part will dive deeper into more complex methods for wayfinding within decision-making scenarios and processes that create confidence and alignment within your surrounding team or teams.

Now that you’ve concluded that you must make the decision, and you’ve exhausted “simple” approaches to break the tie among alternatives, it’s time to introduce more in-depth methods.

I’ll present these frameworks from the least to most complicated. Again, these are not mutually exclusive tools, though each is explained as though it is. Feel free to cherry pick elements from each to create your optimal decision-making tool. (If you do that, please write to me and tell me how it went!)

“Xanax for decision-making”

This approach was popularized by Flatiron Health CTO Gil Shklarski, who learned of it from his executive coach, Marcy Swenson.

As an aside, us coaches are usually sitting on a treasure trove of tools and frameworks for all sorts of life and career problems. But me? I put them all into this blog!

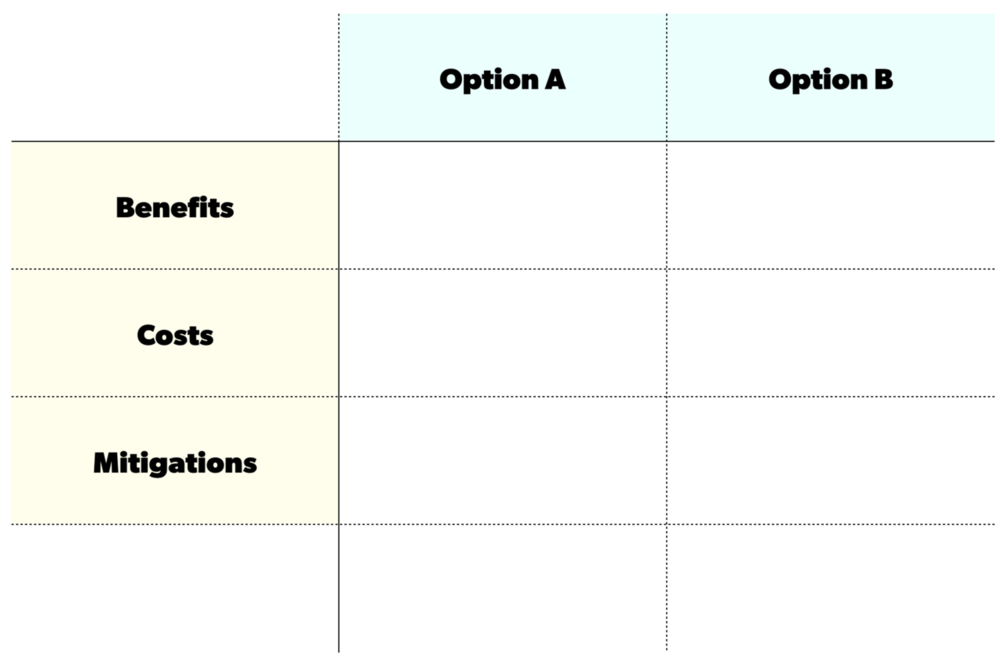

This tool also claims to be a sort of “matrix,” though I’d describe it as more of a table. Shklarski’s goal was to streamline “reversible” decisions at lower levels of the org, so that fewer would bubble up to him as CTO, but I see no reason that this approach could not be used for practically any decision.

That said, if the decision you’re facing is extremely high-risk and irreversible, one of the later frameworks may be a better starting place.

For each option, populate these rows:

Shklarski offers some specific guidance on how to populate this chart:

-

If done as a group, appoint a facilitator to drive participation, ensure everyone is heard (and heard from), and moderate discussion.

-

Benefits and costs should not overlook social considerations or downstream ramifications. For example, who is made happy or unhappy, will some team be energized by the outcome, will someone gain an opportunity?

-

The “cost” row should emphasize not just material costs, but other risks as well.

Finally, in the “mitigations” row, determine how to “soften, allay, or distribute the risks” associated with each option. The facilitator should push the group to really think through what the reality would be if each option were selected.

Considering the risks, ask some questions to drive deeper clarity:

-

What is the root cause, and can we mitigate that?

-

Is there another way to tackle the technical or product debt?

-

What trade-offs are available between the short- and long-term?

More history, detail, and examples can be found on the First Round Review site.

Finally, make a decision. After this structured conversation, it should seem rather clear which is the best alternative. Document what signals you used to arrive at the decision, and be sure everyone receives that information from you.

These types of decisions are seldom unanimous or without dissent. Your responsibility as the decision-maker is to ensure that even dissenters understand what information and logic you applied to reach your conclusion.

S.P.A.D.E.

This technique was built by Gokul Rajaram during his time at Google and later Facebook, then was formalized and widely deployed at Square.

The name stands for Setting, People, Alternatives, Decide, Explain. In this approach, an independent “approver” is recommended. It is that person’s job to verify that this process is correctly followed and ultimately to sign off on the decision; not to approve the outcome that is chosen, but to confirm that it was reached by fairly following these steps.

Gokul points out that this framework is for hard decisions only. If the choice before you is “as simple as selecting a flavor of kombucha,” everyone can save the time and effort necessary to follow this process.

Setting

Define the decision itself in full detail. The Setting comprises three dimensions: what, when, and why. Document each aspect of the decision at issue carefully.

What is the decision, exactly? Be specific. “Which database backend should we standardize our core infrastructure on?” is an OK start, but that sentence implies that there are multiple products to choose from, probably multiple products already in use, and likely more.

Be sure to address every possible dimension of what the decision implies; make the implicit explicit.

When must this decision be made? Choose an actual date, and write the justification for it.

Why does this decision matter? What value is created by arriving at the choice? Cite all stakeholder concerns.

People

Define your RACI, but in the S.P.A.D.E. system, “responsible means accountable,” so you can focus on who must be consulted, who will approve, and who is ultimately responsible.

One person is empowered to make the decision and to own execution and success of the outcome. Whoever is responsible is also accountable.

“One of the most common decision-making pitfalls is under-consulting.” Make space and time to consult broadly. Dissenters will emerge; listen to them and take their feedback into account. Ultimately, dissenters will accept the decision if they were heard.

Alternatives

Generate possibilities that are:

- Feasible and realistic;

- Diverse, not variants of each other; and

- Comprehensive across the problem space

A recommendation given is to brainstorm publicly. Engage everyone in the “consulted” group to generate ideas. Work hard to get to a quantitative impact of each alternative against the “why” in your Setting.

Decide

First, solicit private votes from among the “consulted” group. Difficult decisions likely have controversial outcomes and it’s critical that everyone’s true thoughts are surfaced.

Finally, the “responsible” person (maybe that’s you) makes a decision.

Explain

Lay out the alternatives and your argument for your choice for the “approver.” The approver has the ability to veto the decision if they can show that the decision lacks fidelity or doesn’t address substantial concerns.

Call a “commitment meeting” and explain your decision to everyone who was involved in this process. Some people will not agree; that is normal, because no truly hard decision reaches consensus.

It is suggested that each consulted individual be given an opportunity to “agree” or “disagree” explicitly. Committing to support the decision, whether in agreement or not, publicly in front of your peers, makes it more likely that you’ll execute.

Broadcast the decision broadly, and use it as an opportunity to demonstrate how decisions like this one are made.

For even more detail, you can read Gokul’s S.P.A.D.E. Toolkit webpage.

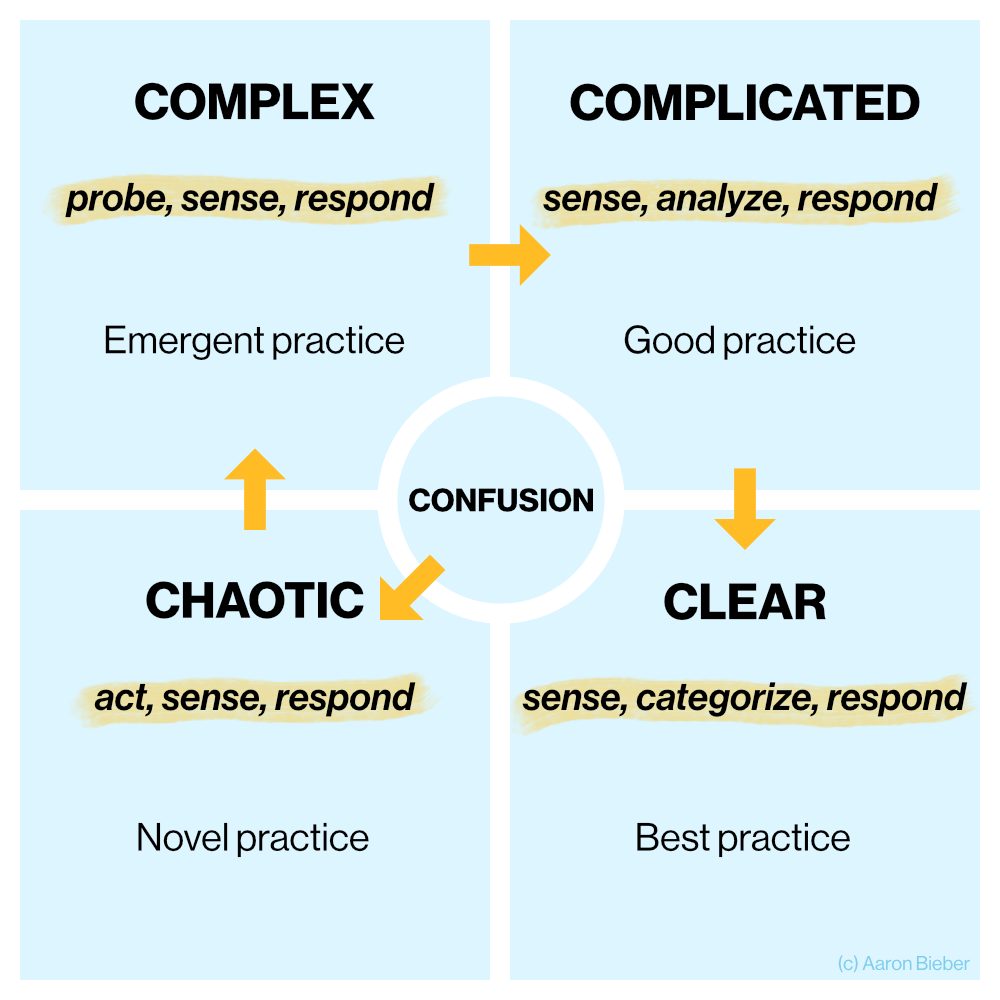

Cynefin

Created in 1999 by Dave Snowden, a Welsh management consultant, during his time at IBM Global Services, the Cynefin (kuh-NEV-in; it’s Welsh for “habitat”) framework has been described as a “sense-making device.”

The purpose of this framework is to provide the decision-maker with a “sense of place” (hence the “habitat” name) from which to understand the steps they must take to move toward resolution. The “sense of place” comes in the form of five “contexts” or “domains.”

The five domains are:

-

Confusion

-

Chaotic

-

Complex

-

Complicated

-

Clear

Confusion is a special case in which there is no clarity about whether any of the other domains fit. This may happen if there are too many leaders involved, or the domain of the problem is simply too broad. Break it down into smaller parts where each one fits into one of the last four domains and can be assigned a single owner.

The goal is to progress through the domains until ultimately all is “clear.” In order to do that, you must acquire new information. How to stabilize the situation and gather information differs in each domain.

I’ll briefly describe each domain, but if you’re interested in this approach, I recommend reading the detailed Wikipedia article about it.

Chaotic

It’s somewhat unlikely that you’ll encounter the chaotic domain in your regular work, but it can happen. In this domain, cause and effect are unclear, and the situation demands that some order be established even in the absence of facts to guide actions.

In a chaotic domain, managers must act, sense, respond. First act to establish some order, then sense where there remains instability, then respond to transform the situation from chaos to complexity.

Complex

A distinguishing characteristic of the complex domain is that there are no right answers. Cause and effect are apparent only in retrospect. In this situation, a manager should look for ways to conduct experiments that are safe to fail, which the framework calls probe, sense, respond.

Complex domains can’t be taken apart or inspected piece-by-piece because any action you take changes the situation in unpredictable ways. Your only option is to experiment, carefully observe, and respond to the best of your abilities.

The goal in probing and sensing is to move from “unknown unknowns” to “known unknowns.”

Complicated

Perhaps the majority of difficult management scenarios lie in the complicated domain, the domain of “known unknowns.” Here, cause and effect can be known, but requires analysis or expertise, and there are a range of right answers.

The framework suggests that managers sense, analyze, respond. Assess what is known, analyze it, and apply good operating practice. This is the domain of specialists (the Wikipedia article names engineers, surgeons, lawyers).

Complicated systems are good fodder for AI, as AIs are able to analyze every possible sequence of moves.

The goal, as always, is to move “known unknowns” to “known knowns.”

Clear

In this domain, all is known, and best practice is established. When all is clear, a manager should sense, categorize, respond. It is simply a matter of understanding what the facts are, mapping them to a known best practice, and doing that.

The goal of the whole framework is to ultimately move all situations into the clear domain over time, using each approach to action and sensing until unknowns are revealed.

The framework authors warn against forcing situations into this domain by oversimplification or complacency. Be cautious not to apply accepted best practice simply because it is established best practice, or to overlook new ways of thinking.

The best method I’ve seen for avoiding that is outlined in the book Art of Action by Stephen Bungay, which describes a method of publishing “briefs” of planned activities and explicitly accepting dissent.

The Cynefin framework authors recommend anonymous dissent, but if satisfactory psychological safety has been established, I have seen open dissent work very well here.

Questions for you

-

When you make a hard decision, does everyone involved know how you made it?

-

How much of your team’s work is in the “clear” domain of best practice? What opportunities exist to move “known unknowns” to “known knowns?”

-

How do you prefer to make decisions?

I’d love to read your answers to any of these questions, please don’t hesitate to comment, write, reply or DM.

Was this useful? Want more? You know what to do!

subscribeFeeling extra grateful? Buy me a coffee!

What would you create if you knew you couldn't fail? I help engineering leaders achieve their impossible dreams. Learn more here.